|

Erin Shirreff, Midday dilemma at Bradley Ertaskiran

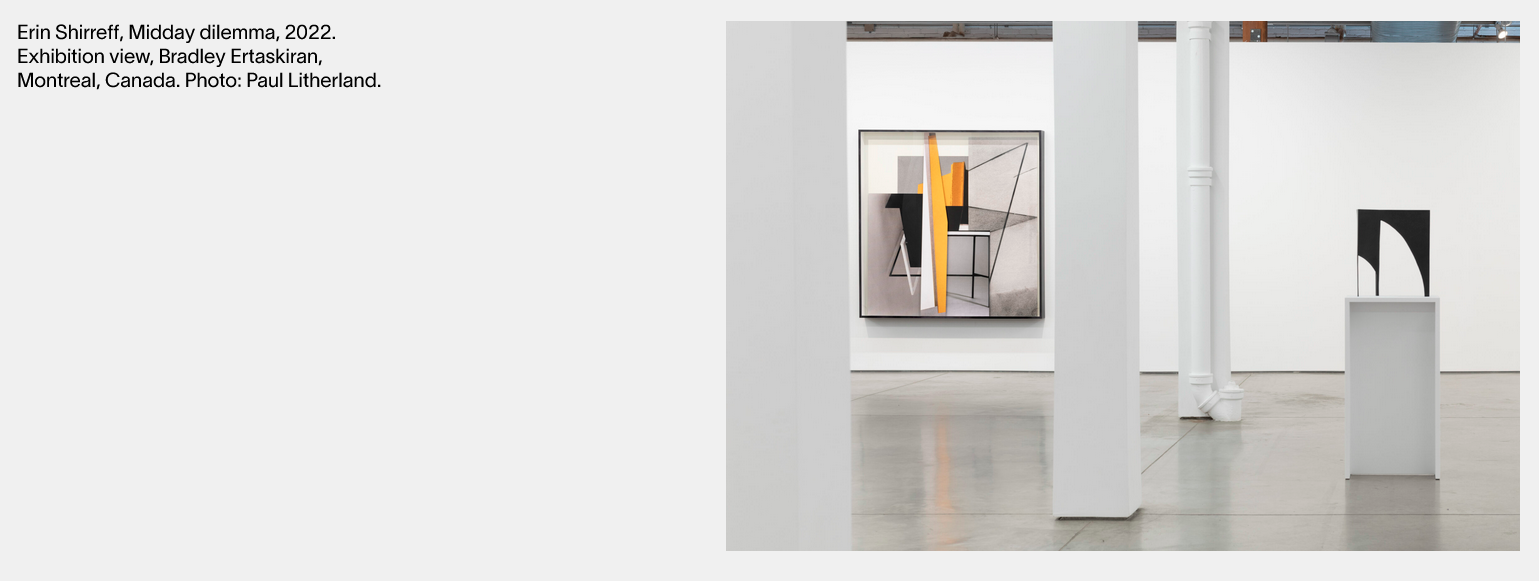

On my way into the Shirreff show on ripped up and mostly vacant Saint-Antoine, two young men pulled up beside me to jovially inform me that Jesus was the messiah. From there, I entered the white noise of the gallery, the textual accompaniment to the exhibition laminated and flatly laying in a corner by the hand sanitizer. At that point, the overwhelming sensation was the stale, sweet smell of forced air.The four wall-works in the exhibition are a mixture of collage and sculptural assemblage constructed from scans of old art anthologies. This imagery was printed on aluminum and cut into shapes then arranged in deep-set frames. Also included are two bronze sculptures inspired by her collages, created using foamcore and hot glue which were then sandcast as single sculptures.

These objects are all sparely placed around the large room, most of the space remaining starkly empty and allowing the visitor to circulate, cutting up the relation between the objects as they do so. The heavy pillar-like beams that dominate the centre of the space also allow one to edit things out by adjusting one’s position, obscuring objects across the room.

Left out of the set list in the accompanying literature was the appearance of five black and white photos evidently taken from magazines or books, set in transparent frames along the walls. These are practically crucial, significantly altering the exhibition’s sense of scale and stressing its objects’ relationship to the transformation of printed matter as primary material. They add a kind of footnote, one that is notable for not actually being explanatory.

Shirreff’s earlier work tended to concern itself (in part) with the way that sculpture was being mediated by photography. Rather than the imposing spatial relation a viewer potentially experiences when encountering a sculpted object, she was more concerned about its quality when it was transformed into a two-dimensional image. This tied it both to a de-familiarization of the expected experience of sculpture as emphatically three-dimensional and the highly familiar sensation of engaging with art through its meditation, especially in books and magazines.

As a result, on one level the work was about how this moment of encounter would be fundamentally different given its architectonic framing, either by book or gallery as its medium. While critics tended to speak of this in terms of what photography is doing to sculpture, the presence of her works tends to put most of the weight on the inverse relation.

The possibilities of blurring photography and sculpture have been a matter of contention since at least the 1970s when the role of both of these practices was debated within the context of Minimalism and Conceptual Art. What Shirreff does seems very different from the attempts by artists working in those loose frameworks to think through the question of medium and its relationship to art history more broadly.

Shirreff’s breaking of objects while simultaneously making them concrete re-enacts dematerialization via materialization, in effect negating the basic conceptual gesture by transforming it into a residuum that trumps its conceptualization: it's a kind of revenge of the object that transforms it into an example (literally: parallel cases, models, illustrations of method) rather an image.